|

|

|

|

|

By Rabbi Marvin Hier

Dean and Founder

Simon Wiesenthal Center

2003

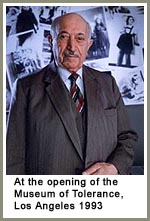

This year marks the 25th anniversary of the creation of the Simon Wiesenthal Center named in honor of Simon Wiesenthal who is now in his 95th year.

When I first had the idea to create an institution that would preserve the memory of the Holocaust, I wondered for whom such an institution should be named.

That's when I thought of Simon who I first met in the 1960's. He was born in a little town called Buchach, Poland into a religious family and studied in a cheder before going to University. Refused entry at the University of L'vov because of antisemitic quotas, he went on to the University of Prague where he graduated in 1932 as an architectural engineer. But he never got to practice his life's passion. His plans were tragically interrupted when one day, Himmler's killers arrived and forced him into a cattle car, taking him on a journey to some of the most infamous places ever known in all the annals of humankind.

Miraculously surviving the tortures inflicted upon his body and soul, he was carried out of Mauthausen concentration camp weighing less then 90 lbs and having paid the supreme price of losing 89 members of his family.

Now as the whole world went home to forget, he alone stayed behind to remember. Shedding his identity from one who designs homes and beautifies communities, to one who investigates those who destroyed them.

Never trained for such a task, he gladly accepted its burden. Causing his wife Cilia to reflect that in addition to herself, her husband was married to the six million victims that perished. Unable to let go of those terrible memories that haunted him. Especially the memory of having chased after the cattle car that carted off his beloved mother to the death camps without her ever knowing of his desperate attempt to run after the train in order to bid her a final farewell.

One day after the war ended on May 9, 1945, he wrote a letter to United States Army intelligence offering his services. He became the permanent representative of the victims. There was no press conference, and no president or prime minister who announced his appointment. He just assumed the job. It was a job no one else wanted.

He began his work with the Army, then set up a small office in Linz, and finally moved it to Vienna. The task was overwhelming and the cause of memory in those days had few friends. The Allies had moved on and were now focused on the Cold War. The survivors were trying to put their lives back together. There were no great films to spur interest, no great writers on the Holocaust to stir the conscience, just a single survivor with no resources who had assumed the role of both prosecutor and detective. Retaining his sense of humor and singular purpose, he went out in search of the perpetrators of genocide.

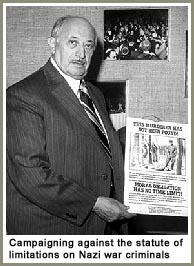

In the end, this architect from Buchach helped bring hundreds of Nazi war criminals to justice. Not just ordinary criminals. People like Franz Stangle, the commandant of Treblinka; Gustav Wagner, the commandant of Sobibor; and Walter Rauf, the inventor of the mobile gas vans who had murdered hundreds of thousands.

But more significantly, he kept alive the torch of memory, not without considerable personal sacrifice, preserving a place in our hearts for the victims of the Holocaust. If there are places today that educate the young about man's inhumanity, it was Simon Wiesenthal who helped plant some of those seeds.

In 1981, together with a group of survivors in Los Angeles, we thought it would be a fitting token of esteem for his work if we could present him with a special gift, a Torah that was rescued from the ashes of the Holocaust. When asked why we preferred an old scroll? I replied, "We want him to have a Torah that was written by a representative of the millions who perished. A scroll that is a remnant of a world that was. A world when Vilna and Krakow still bustled with Jewish pride. When mothers still sang their lullabies. When scholars studied, poets dreamed and philosophers reasoned late into the night. A scroll that was witness to the black smoke that sealed the fate of an entire civilization. A scroll that can say - Simon! If there are still those out there who find meaning in the way we once lived, it is a tribute to you who never let the world forget the way we died."

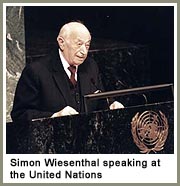

In August of 2000, at a ceremony at the White House, I was privileged to accept on his behalf, the Medal of Freedom, the U.S.'s highest civilian recognition presented by the President of the United States. He was only the sixth foreign citizen in the history of the U.S to be so honored. In a letter, which I handed to President Clinton on his behalf, he wrote, "My cause is justice, not vengeance. My work is for a better tomorrow and a more secure future for our children and grandchildren who will follow us. As a firm believer that each of us are accountable before our creator, I believe that when my life has ended, I shall one day be called to meet up with those who perished and they will undoubtedly ask me, 'What have you done?' At that moment, I will have the honor of stepping forward and saying to them, I have never forgotten you."

As you enter your 95th year, we are here to say, neither has the world forgotten you, Simon.